Are there rules for writing a sales letter? Then what would be the basic rules of writing sales letter? There can be no ‘one size fits all’ formula. However, there may be certain guidelines and best practices, which one can follow.

A study, recently completed, of tabulated return; from pieces of sales literature seem to offer convincing proof that there are certain fundamental principles which successful sales literature including sales motivation letter or sales cover letter follows.

These principles have been analyzed and reduced to rules. The rules themselves are stated in this article.

The Basic Rules of Letter Writing

The fact that these basic rules of writing sales letter have been worked out from a careful study of a significant number of pieces of sales literature—both successful and unsuccessful—is in itself proof that these rules are not mere flash-in-the-pan statements of sup- posed principles. But a still further test has been applied—a psychological and highly scientific test.

The test proves that the rules are basic, because each one of them, independent of the others, may be deduced from one central psychological process—the psycho-physical reaction, as it is called.

The full meaning of these terms, and the psychological problems involved, will be clearly explained as soon as the rules themselves are given.

Rules of writing sales letter

Sales literature such as sales motivation letter or sales cover letter, when it is written in accordance with these rules, is invariably more effective than when it ignores them or fails to take them properly into account. The same is true of collection and adjustment letters, and very largely of advertising in general, for after all these are only specialized forms of sales literature.

Expert Sales Literature Not Always Successful

It does not follow, however, that sales literature written even with expert application of these principles of correspondence will invariably be successful. The most that can be said for such literature is that it has a good fighting chance. Under normal conditions and to well- chosen trade prospects, it will succeed.

Under adverse conditions, such as the outbreak of war or any more or less transient social excitement, failure may result.

Furthermore, a letter or advertisement may succeed even though it contradicts one or more of these principles. But this fact does not shake the principles themselves. Such a letter would be more successful if its faults had been corrected. This truth has been proven by experiments.

The rules, which apply rather to the thought than to the way in which the thought is expressed, are six in number. Anyone who has to judge the value of a business letter before it is mailed will find in them tools far more significant than his own individual preference or dislikes.

Avoid Debatable Statements

Never assert in any way in your letter that which is debatable or untrue. In other words, never give the potential client a chance to argue, to doubt you, or to say “no.”

Every sentence and paragraph is to be so written that the prospect/potential client must admit its truth. There is a danger, for instance, in saying “You are a busy man,” or “You have seen our letters.” You do not know these facts for certain.

You can get around the difficulty by adding “doubtless” or a similar qualifying phrase, which makes your sentence absolutely true. The significance of this principle will probably not become entirely clear, however, until we come later to the underlying psychology of the matter. The same is true, in part, of the five rules following.

Maintain Continuity of Thought

Never check or interrupt the steady flow of your prospect’s thought. An ambiguous statement, or a statement that has not been introduced logically earlier in your letter, does just this.

Do not allow these “breaks” in your letter. In the opening paragraphs, express or imply everything that the letter as a whole is to contain—every idea it is going to convey to the prospect’s mind.

‘Use a Whip‘

Make your sales motivation letters or sales cover letters easy to read. A western sales office shortens this statement, and says, “Use a whip.” The idea is simple in practice, because all you have to do is to break your letter up into many paragraphs, separating long or tedious paragraphs with contrasting short and easy ones.

But take care to have these short paragraphs packed with significant meaning. When an engineer is constructing an automobile road up a hill, he does not usually make just a single gradual incline. First he has a rather steep incline, then a flatter incline, in order that the driver may let his machine gather new momentum for the next steep incline; and so on to the top.

Solid type on a page is, to the average reader, like a single long incline to the motorist. Short paragraphs, on the other hand, serve as rests and keep the reader’s interest alive and active.

Leave Nothing to the Imagination

In every letter, give or imply all the facts about your proposition that the reader could possibly want to know. Perhaps a better way to put this rule would be: make clear, either by what you actually say or by what you imply, every service that your proposition is capable of rendering the prospect.

In practice, it usually works out that the potential client/prospect is satisfied after he is sold on some one point which happens to interest him most, all the other points being more or less distinctly grouped and valued equally with this one satisfactory point in his mind.

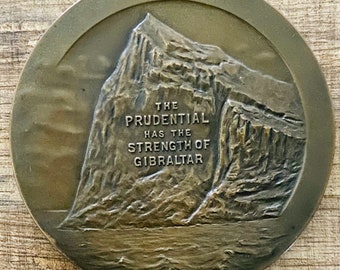

Slogans in advertising often illustrate this rule. Take, for example, “The Prudential has the strength of Gibraltar.” This slogan makes a direct assertion. But, In addition, it indirectly implies that the concern in question has all the virtues of any other concern.

The complete assertion is, perhaps, “The Prudential has all the prospect could possibly find in any other company, and in addition it has the strength of Gibraltar.” This, at least, is the effect on the reader. So the slogan set a forth, partly expressed and partly implied, the full service toward which its promoters strive.

It is precisely in this sense that the fourth rule is to be understood. In a letter, the host of particular services that the proposition will render the prospect can, in a similar way, be grouped in larger and larger classes, until a paragraph or a sentence, or even a single word, will denote all of them.

Avoid Alternative Offers

Avoid confusing the prospect by presenting to him a series of propositions from which he must make a selection. Avoid alternative offers, in other words.

The reason for this rule is a matter of psychology and will be discussed later. Meanwhile, there is one qualification to the rule: there may be cases where the writer will find he must make such offers.

It remains generally true, nevertheless, that an appeal made on one issue alone is more effective than an appeal where the prospect has to make a choice. This can be proved by anyone who cares to experiment.

The way to avoid choice offers is a “list problem” – divide your prospects rather than your offer.

Make Only Positive Assertions

Make your letter portray advantages to be gained, instead of evils to be avoided. Be positive, rather than negative. In the business world it is perhaps easier to threaten and scold than to be constructive, just as it sometimes is in the nursery.

But the best results come when you think out some positive benefit your prospect will receive when he does what you want him to do. These, then, are the six principles. They cover the important aspects of letter-writing. An explanation of the psychological processes on which they rest will help make them clear.

The underlying principle from which the six principles may be deduced — a principle which every letter writer will do well to keep in mind — is called the psycho-physical process or reaction.

Psycho-physical Reactions

In practice, to be sure, every sale, collection or adjustment, from the point of view of the prospect, is a complex process involving possibly hundreds of subsidiary psycho-physical reactions; but it is not necessary to go into that.

It is enough to regard each one of these series of processes only as a simple combination of three elements:

(a) Nervous currents running into the brain (stimulus) ; (b) Brain excitations; (c) Nervous currents running out from the brain (discharges).

All this is physiological. There is in addition the consciousness which accompanies the brain excitation, but is not a part of it. To touch a hot object, for example, to feel the heat, the pain, and to withdraw the hand, is a psycho-physical reaction.

So also is the experience of seeing an object, and recognizing it as a book or a picture. So also, even if in a much more complex form, is the act of receiving, opening, reading and answering or throwing away a sales letter.

This last action, to repeat, is as a matter of fact a whole series of psycho-physical reactions; but for the present purpose it may be considered a single, simple process.

Now, what has all this to do with the simple, every day necessity of writing sales letters that will get orders?

Just this: it follows that every word and sentence in your letter, circular or advertisement should seek: first, to start one of these psycho-physical processes; second, to build it up slowly and carefully by degrees until the brain excitation is sufficient to break over and permit the third element in the process to result in a discharge in favor of your proposition.

When that happens, a sales letter results in a sale; a collection letter brings a remittance, or at least a response; an adjustment letter successfully handles a complaint.

The Use of Strategy

So it is successful strategy to put into the sales letter whatever will hasten the development, and increase the extent, of this favorable brain excitation (and the corresponding mental ideas and feelings). On the other hand, bad salesmanship puts into the letter something that hinders this favor- able psycho-physical process, or cuts off such a development entirely.

This, then, is the psychological background. Some people balk at the word “psychology.” They apparently believe that big words hide little ideas, and theory for- gets practice. Well, let us see what these psychological principles have to do with the six rules given above: how they help the development of something like a real science of business correspondence; and how, finally, such science will help you and me to write letters that bring a higher percentage of returns.

Moulding Your Prospect’s Opinion

Take the first rule. It asserts, you will remember, that under no conditions should your letter contain a statement which the prospect can deny. One apparent exception to this is the case where the correspondent may feel it is absolutely necessary to assert something which his prospect might deny.

From the point of view of the whole letter, making such an assertion may be all right. This is especially true if you can make several assertions which the prospect must admit, leading up with them logically to the assertion which you fear your prospect may deny.

Then if he does deny it, he must confess himself at fault in having admitted the previous assertions. A strong close may often be developed by such handling.

Leaving this question aside, however, what happens — psychologically — when a prospect comes across a sentence or assertion that is not convincing?

At once there arises in his mind a conflict, which is in reality an antagonistic psycho-physical process. The very existence of such a process, however slight, is a detriment to the letter’s chances; it hinders the development and completion of the first favorable process.

One Idea at a Time

Only one idea can occupy the prospect’s attention at any one instant, and when two or more Ideas are pressing they pull against one another. The stronger the antagonistic process is, the less opportunity is there for the sales letter to succeed.

In psychological terms, the favorable process is crowded out; no “discharge” is possible. In everyday terms, the prospect does not mail the order you want him to. This is the reason why the letter writer must use extreme care to put in the mind of the prospect only such ideas as he wants to have there, and why he must guard against letting in ideas which are opposed to his purpose.

The prospect is only too liable to let these suggestions jump into his consciousness, without your suggesting them. As an apparently harmless phrase often has an unsuspected “kick” to it, the importance of choosing writers who are naturally tactful and then training them to know the viewpoint of their readers is evident.

To keep out of the reader’s brain any process other than the one you wish to foster is not enough, however, to advance this desirable process. The ideas in the letter must actively excite his brain in the desired direction.

So you must put into your letter as much “meat” or “stuff” or “punch” as possible. If these word-images are properly chosen, they will pull up hosts of other associated images. These are all valuable in building up the favorable process toward the point of discharge.

Psychology of the Second Rule

There may be danger here, however. To guard against it, the second rule of correspondence comes into play. That rule, you recall, is not to allow “breaks” in your letter. By “break” is meant any unusual phraseology which stops the prospect’s flow of thought, or any new thought or idea which is unexpected because it has not been implied earlier in the letter.

It is obvious that when such a break occurs, the mental process you have been striving to build up in your prospect’s mind is broken down, and a new process has to be built up. In other words, you have to start all over again to sell the prospect, if you make a break of this kind. Naturally, this works against your success. It is like throwing water on a fire you are trying to make burn.

The first two rules are negative. They point out grave dangers that always confront correspondents.

They indicate the means that may be used to avoid retarding the psycho-physical process that is to terminate in the sale, the collection or the adjustment.

The Why of the Third Rule

What are the positive things that help the process along—accelerate its development? The third rule is the answer: “Use a whip.” This principle should be understood in a double sense. On the one hand, it has to do with the physical structure of the letter. The letter ought to lock easy to read. It should be so worded and paragraphed that it is easy to read, for solid type is uninviting and hard on the eyes.

But there is, on the other hand, a psychological as well as physiological reason for the rule. In exactly the same way that a whip stirs you up if you are hit by it, so the thought in your letter ought to stir up your prospect’s mind. And snappy paragraphs always have this definite value if you summarize what has gone before, and prepare for what is coming.

They are psychological “level grades” like those that help the motorist en a steep hill—a kind of mental breathing place. It is a significant fact that the most successful letters out of the forty million had these “whips” in the largest number.

It may be added, in passing, that the psychological “whip” can be present in a letter even if the short, sharp paragraphs are not used.

Stimulating Brain Excitement

The fourth of the rules of writing sales letter, like the third, is positive. I will repeat it for the sake of clearness: In every letter give or imply all the facts about your proposition that the reader could possibly want to know. The idea, of course, is to make the amount of favorable brain excitement, and the mental excitement as well, as large as possible.

The more excitement there is, remember, the greater is the likelihood of the favorable discharge you wish for. In other words, if you get your man all worked up, you are more likely to receive the order. So, if you get the interest of a prospect at all, the greater the number of favorable points you can bring to his attention the better.

The limit of this policy, plainly, is the complete service your proposition can render. So this fourth principle is not merely helpful—it is basic. In this connection there are a few incidental helps for correspondents which are perhaps worth noting here.

For example, whatever serves most to develop imagery helps your letter. Nouns, therefore—as many of them as possible—are good. They represent objects or things, and these always induce images.

The right use of adjectives helps also. Adjectives can always be used to qualify nouns, or to give the meaning a novel twist or limitation. Indeed, one successful correspondent says, “It’s adjectives that put the punch in a letter.” Repetition is a third means.

Judicious restatement of any thought, if not carried to the point of weariness, is effective. Especially valuable is it when prospects are likely to be skeptical about your proposition. In loaning money, selling bonds or real estate, for example, or whenever an important point has to be emphasized, this rule applies.

Alternative Offers Shift Attention

Regarding the fifth rule, it has already been pointed out that it may not always be possible to avoid offers involving a choice. Take the catalogs which mail order houses use, for example. Many of the articles listed could not be advertised separately, because of the relatively great expense.

This is one case where it is not possible to follow the rule literally. But in general the rule proves true, psychologically.

Only one process can occupy the prospect’s attention at one time. It obviously follows that a selective proposition requires consideration first of one offer and at a later moment of the other. In order, therefore, to consider two or more propositions the prospect must continually be shifting his attention.

Furthermore, when the final moment of choice comes, and the prospect weighs the various propositions you have put up to him, a new law of psychology comes into play. This law brings out the fact that neither idea can become so clear and strong as either one of them might become by itself.

This rule of writing sales letter has been proved in practice as well as in psychology, for sales propositions with choices and without choices have been tried out, and—other things being equal—the alternative offer never does so well as one allowing no choice.

Emphasize Positive Advantages, Not Negative

The last of rules of writing sales letter is slightly different from the others. You will recall that it suggests portraying in your letter advantages which the prospect will secure if he takes up with your proposition, rather than portraying evils he will avoid. Psychologically, what is the reason for this rule? A complete explanation would call for a lot of technical phraseology, but a brief outline will suffice.

Feelings, as well as mental images, are correlated to brain states. And, roughly speaking, pleasant feelings occur when the nervous currents running out of the brain discharge into the muscles of the body which cause the limbs to open or extend—the extensor muscles.

Unpleasant feelings occur when the nervous currents discharge into the flexor muscles: the muscles which cause the limbs to close. Everyday illustrations of this fact are numerous. “The glad hand,” for example, is an open hand—open because the nervous discharges are going into the extensor muscles.

On the other hand, clenched fists, a drawn face and a crouching figure are almost certain signs of the opposite kind of feelings. In general, these two kinds of feeling denote, respectively, the two attitudes which we call positive and negative. And a positive letter is one that induces pleasant feelings; a negative letter one that induces unpleasant feelings.

The positive letter pictures desirable things which may be secured by the action suggested in the letter. The negative letter speaks only of undesirable things, which are to be avoided. Good salesmen, perhaps unconsciously, know it pays to be positive. Before they try to sell a man, they make an effort to get him in good humor.

The whole point, of course, is simply that when you work from the negative angle you encounter resistance due to the contracting attitude which you have to overcome before any favorable action is possible.

And, of course, writing a check or signing an order is a favorable action, accomplished only when the attitude is positive and discharges are going into the extensor muscles.

Forcing an order from a man, of course, might be an exception. But you cannot force orders by mail — they must be earned by carefully built persuasion.